From The Birmingham (AL) News

This GOOD news:

Last of nerve agent at Anniston Depot destroyed

2 million pounds of mustard agent left

Thursday, December 25, 2008

KENT FAULK

News staff writer

ANNISTON - The last of the deadly nerve agent weapons in the chemical weapons stockpile at Anniston Army Depot were incinerated Wednesday.

Destruction of all the nerve agent weapons means that more than 99 percent of the risk the stockpile posed to the community is gone, incinerator officials said.

"With the VX mines gone, there is realistically no risk for the community," said Timothy K. Garrett, site project manager at the Anniston Chemical Agent Disposal Facility.

Incinerator employees gathered in the control room to watch on monitors at 11:51 a.m. as the final M23 mine began its trip along a conveyor to be incinerated.

A munitions handler had written "Last Mine" and "Good Bye" on the top of the mine, and "End of VX Munitions" and the names of companies involved in the incineration on the bottom, before placing it on the conveyor system.

Seven minutes later, after machines sucked the VX out and into a liquid tank for incineration, the mine was dropped into another incinerator.

"Congratulations, guys. Merry Christmas to you," Robert C. Love, project manager for prime contractor Westinghouse, said to the group of employees.

Destruction of the last of the nerve agent was good news Wednesday for officials in Calhoun County, where residents have lived with the stockpile for nearly a half century and its incineration for the past five years.

"That's wonderful. It couldn't have happened any too soon," said Calhoun County Commissioner J.D. Hess.

The most recent batch of weapons destroyed consisted of 44,131 land mines filled with the VX nerve agent. Incineration of the land mines was about eight months ahead of schedule, Love said.

With the completion of this phase of the destruction, 54.6 percent of the stockpile has been incinerated, said Mike Abrams, a spokesman for the Army. In all, 361,802 munitions and 293,003 gallons of nerve agent have been destroyed. That includes 219,374 VX-filled munitions and 142,428 GB-filled munitions.

Workers now begin preparing machinery to destroy the remainder of the stockpile - World War II-era mortars, artillery and containers with nearly 2 million pounds of mustard agent. Incineration of mustard agent weapons is scheduled to begin in the next five to seven months but could begin sooner.

Mustard agent doesn't cause problems unless someone comes in direct contact with it, and that's why there is less threat to the public than with the nerve agents, Garrett said.

Workers will be trying to finish the mustard agent incineration by April 29, 2012, to meet the deadline in an international treaty to destroy stockpiled chemical weapons, he said. After destruction of the mustard agent weapons, the incinerator will be dismantled in a process that will take a few more years.

Monday, December 29, 2008

Saturday, December 27, 2008

Front Page - Above The Fold

From the Desert Sun:

December 26, 2008

Palm Springs man helping to clear Cambodia of explosives

Stefanie Frith

The Desert Sun

The humidity is intense. More than 80 percent, on top of the 90-degree weather. He uses a kroma — a thin scarf — to wipe the sweat out of his blue eyes and over his closely cropped gray hair. He carries rice, water, Spam, Cup of Noodles, coffee and tea on his back. Maybe tonight there will be something else to eat with it other than rat.

The humidity is intense. More than 80 percent, on top of the 90-degree weather. He uses a kroma — a thin scarf — to wipe the sweat out of his blue eyes and over his closely cropped gray hair. He carries rice, water, Spam, Cup of Noodles, coffee and tea on his back. Maybe tonight there will be something else to eat with it other than rat.

Ahead of him in the Cambodian jungle, one of the metal detectors goes off with a “wow, wow” sound. A land mine has been found. Palm Springs resident Bill Morse never thought he would be running a charity to help clear the unexploded bombs and land mines in Cambodia.

He owned a marketing and sales consulting business, which he closed last year to focus his efforts in Cambodia. Now he spends up to eight months a year working in Cambodia, in the Landmine Relief Fund office or in the jungle, clearing land mines, eating whatever he can catch, and sleeping in huts or on the ground.

“There is a perception that Cambodia is handling it,” Morse said recently, sitting in his living room, surrounded by artifacts from his trips around the world. “Our objective is to clear land mines in low-priority villages.”

The land mines and bombs are from when the United States infiltrated the country and when the Khmer Rouge was in power in the 1970s, Morse said.

More than 500 people were injured from exploding land mines in Cambodia last year, Morse said. An estimated one in every 250 Cambodians has been injured since the 1980s, he said.

Finding Aki Ra

Five years ago, Morse traveled to Cambodia. He had heard of a man named Aki Ra from a friend who had raised money to buy him a metal detector so he didn't have to search for land mines by hand.

Aki Ra has cleared 50,000 land mines — and still has all his limbs. By age 5, he was orphaned. By age 10, he was fighting with the Khmer army, laying the land mines he would later seek to eliminate. When he was a soldier, he could lay 1,000 land mines a day. “Nobody kept a record,” Morse said.

He survived the genocide that killed 1.7 million Cambodians between 1975 and 1979 — more than 20 percent of the country's population, according to Yale University's Cambodia Genocide Program.

It wasn't easy finding Aki Ra. He ran a land mine museum on a dirt road, but the hotel concierge either didn't know of it, or wouldn't tell Morse where it was. When he did find him, Morse said he was overwhelmed by this man, and knew he had to help.

Morse not only set up the Landmine Relief Fund and became its director, but he returned to Cambodia to help Aki Ra with international certification. He joined Aki Ra in the jungle, hunted for meals as they looked for land mines, and stood by his side as he located them in the ground.

“You dig the hole at an angle, so if you hit the land mine, you hit it on the side,” Morse said.

Land mines were never designed to kill, said Morse, who spent a year in the U.S. Army. Injuring people was more effective in the war — as the injured had to be carried by at least two people. This is not to say the mines haven't killed.

Recently, Aki Ra was clearing land mines in a village when the government ordered him to stop. Shortly after, five people were killed when their truck went over one.

Morse spends several months a year in Cambodia, working in the Landmine Relief Fund office and in the jungle with Aki Ra and a five-member crew. When land mines are found, the area is roped off and the devices are blown up. Morse said he used to stand next to Aki Ra as he did his work.

Now, with recent government accreditation, Morse said he goes into the area last and documents what the team does. It takes a team of five to clear the mines — four people are needed to carry a stretcher — he said.

There are several land mine clearing organizations in Cambodia. The issue gained prominence when Princess Diana campaigned for the clearing of devices. There are also several groups affiliated with the cause. Project Enlighten provides educational opportunities for children in Cambodia, including those living at the Landmine Museum run by Aki Ra. Project Enlighten Founder Asad Rahman knows Morse well and said he is one of the “most honest and driven men” with whom he has worked. “His vision and passion to help eradicate the land mine issue is unparalleled. He is a saint,” Rahman wrote in an e-mail from Laos to The Desert Sun.

Morse only wishes he could do more. Donations have dribbled recently and he said he would like to have a celebrity step in as a spokesperson to help gain publicity for the cause. He wants to raise $45,000 to put another team of five into the Cambodian jungles. “I couldn't think of a better way to spend my money and my time. We are going after the stuff we left there. I'm (just) a janitor.”

For more information, or to make a donation, visit

http://www.landmine-relief-fund.com/ or http://www.cambodialandminemuseum.org/.

Landmine Relief Fund,

P.O. Box 4904,

Palm Springs, CA 92263.

December 26, 2008

Palm Springs man helping to clear Cambodia of explosives

Stefanie Frith

The Desert Sun

The humidity is intense. More than 80 percent, on top of the 90-degree weather. He uses a kroma — a thin scarf — to wipe the sweat out of his blue eyes and over his closely cropped gray hair. He carries rice, water, Spam, Cup of Noodles, coffee and tea on his back. Maybe tonight there will be something else to eat with it other than rat.

The humidity is intense. More than 80 percent, on top of the 90-degree weather. He uses a kroma — a thin scarf — to wipe the sweat out of his blue eyes and over his closely cropped gray hair. He carries rice, water, Spam, Cup of Noodles, coffee and tea on his back. Maybe tonight there will be something else to eat with it other than rat.Ahead of him in the Cambodian jungle, one of the metal detectors goes off with a “wow, wow” sound. A land mine has been found. Palm Springs resident Bill Morse never thought he would be running a charity to help clear the unexploded bombs and land mines in Cambodia.

He owned a marketing and sales consulting business, which he closed last year to focus his efforts in Cambodia. Now he spends up to eight months a year working in Cambodia, in the Landmine Relief Fund office or in the jungle, clearing land mines, eating whatever he can catch, and sleeping in huts or on the ground.

“There is a perception that Cambodia is handling it,” Morse said recently, sitting in his living room, surrounded by artifacts from his trips around the world. “Our objective is to clear land mines in low-priority villages.”

The land mines and bombs are from when the United States infiltrated the country and when the Khmer Rouge was in power in the 1970s, Morse said.

More than 500 people were injured from exploding land mines in Cambodia last year, Morse said. An estimated one in every 250 Cambodians has been injured since the 1980s, he said.

Finding Aki Ra

Five years ago, Morse traveled to Cambodia. He had heard of a man named Aki Ra from a friend who had raised money to buy him a metal detector so he didn't have to search for land mines by hand.

Aki Ra has cleared 50,000 land mines — and still has all his limbs. By age 5, he was orphaned. By age 10, he was fighting with the Khmer army, laying the land mines he would later seek to eliminate. When he was a soldier, he could lay 1,000 land mines a day. “Nobody kept a record,” Morse said.

He survived the genocide that killed 1.7 million Cambodians between 1975 and 1979 — more than 20 percent of the country's population, according to Yale University's Cambodia Genocide Program.

It wasn't easy finding Aki Ra. He ran a land mine museum on a dirt road, but the hotel concierge either didn't know of it, or wouldn't tell Morse where it was. When he did find him, Morse said he was overwhelmed by this man, and knew he had to help.

Morse not only set up the Landmine Relief Fund and became its director, but he returned to Cambodia to help Aki Ra with international certification. He joined Aki Ra in the jungle, hunted for meals as they looked for land mines, and stood by his side as he located them in the ground.

“You dig the hole at an angle, so if you hit the land mine, you hit it on the side,” Morse said.

Land mines were never designed to kill, said Morse, who spent a year in the U.S. Army. Injuring people was more effective in the war — as the injured had to be carried by at least two people. This is not to say the mines haven't killed.

Recently, Aki Ra was clearing land mines in a village when the government ordered him to stop. Shortly after, five people were killed when their truck went over one.

Morse spends several months a year in Cambodia, working in the Landmine Relief Fund office and in the jungle with Aki Ra and a five-member crew. When land mines are found, the area is roped off and the devices are blown up. Morse said he used to stand next to Aki Ra as he did his work.

Now, with recent government accreditation, Morse said he goes into the area last and documents what the team does. It takes a team of five to clear the mines — four people are needed to carry a stretcher — he said.

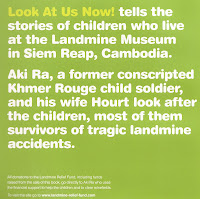

There are several land mine clearing organizations in Cambodia. The issue gained prominence when Princess Diana campaigned for the clearing of devices. There are also several groups affiliated with the cause. Project Enlighten provides educational opportunities for children in Cambodia, including those living at the Landmine Museum run by Aki Ra. Project Enlighten Founder Asad Rahman knows Morse well and said he is one of the “most honest and driven men” with whom he has worked. “His vision and passion to help eradicate the land mine issue is unparalleled. He is a saint,” Rahman wrote in an e-mail from Laos to The Desert Sun.

Morse only wishes he could do more. Donations have dribbled recently and he said he would like to have a celebrity step in as a spokesperson to help gain publicity for the cause. He wants to raise $45,000 to put another team of five into the Cambodian jungles. “I couldn't think of a better way to spend my money and my time. We are going after the stuff we left there. I'm (just) a janitor.”

For more information, or to make a donation, visit

http://www.landmine-relief-fund.com/ or http://www.cambodialandminemuseum.org/.

Landmine Relief Fund,

P.O. Box 4904,

Palm Springs, CA 92263.

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Donate Today - Change a Life Tomorrow!

Cambodian Self Help Demining Is clearing Kokchambok Village

It will take us 4 months and cost $20,000 to change the lives of the villagers of this "low priority" villagein the heart of Cambodia.

They've already lost 5 dead, 3 woulded and 15 cattle.

We will change their lives and you can help...right now.

For a donation of $50 or more we will send you a CSHD window decal .

For a donation of $100 or more we will send you a copy of “Look at us now!” - The Children’s Story (and a decal)

For a donation of $200 or more we will send you a copy of Beth Pielert’s Film, “Out of the Poison Tree” featuring Aki Ra. (and a decal and a book)

Donate at:

http://www.landmine-relief-fund.com/relief-fund.com/

Click on the PayPal Button

Thanks

Babu

Thursday, December 4, 2008

Cluster Bombs - the gift that keeps giving

The first cluster bombs were dropped on Grimsby, England by the Luftwaffe in 1943. They have been a staple of war since.

During the Vietnam War the United states dropped over 383,000,000 cluster munitions on Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. It's been estimated that as many as 30% failed to explode on impact and are just waiting for some unsuspecting civilian to discover.

If those figures are only half right, there are 57,000,000 unexploded cluster munitions littering SE Asia.

Cluster bombs are not considered landmines, although they are unexploded munitions lying on the ground, that explode, maim and kill when disturbed.

If it walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck...........

100 nations are meeting in Oslo, Norway today. They are signing an international treaty to ban the use of cluster munitions.

The United States is NOT signing the treaty. We did NOT sign the treaty banning landmines.

We still use cluster munitions. We still use landmines.

And we still are not cleaning up our mess.

We leave that for the innocents to do.

Shame on us.

Bill

Janitor

During the Vietnam War the United states dropped over 383,000,000 cluster munitions on Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. It's been estimated that as many as 30% failed to explode on impact and are just waiting for some unsuspecting civilian to discover.

If those figures are only half right, there are 57,000,000 unexploded cluster munitions littering SE Asia.

Cluster bombs are not considered landmines, although they are unexploded munitions lying on the ground, that explode, maim and kill when disturbed.

If it walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck...........

100 nations are meeting in Oslo, Norway today. They are signing an international treaty to ban the use of cluster munitions.

The United States is NOT signing the treaty. We did NOT sign the treaty banning landmines.

We still use cluster munitions. We still use landmines.

And we still are not cleaning up our mess.

We leave that for the innocents to do.

Shame on us.

Bill

Janitor

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)